Firstly, the conclusions, mainly for two reasons:

- Historical reasons: British colonizers disrupted Myanmar's once smooth state-building.

- Resource/Dictatorial reasons: Myanmar's leaders, headed by Than Shwe, have heavily exploited natural resources to enrich themselves and strengthen brainwashing and totalitarian rule.

The recent movie "No More Bets" is gaining popularity; it is about a fraud syndicate in northern Myanmar. A good friend of mine who works in Hong Kong was planning to visit Thailand. She told me she feared being kidnapped to Myanmar. I think it's indeed possible, not just because she is so attractive, but also due to the current global economic downturn. In resource-rich, dictatorial countries, where the cost of crime is so low, if I were a street thug in Thailand with no hope in sight, I would definitely seize the opportunity to kidnap someone. Whether or not I would get caught or executed is not up to me. After all, being born in purely dictatorial countries like Myanmar, Thailand, or Laos, there’s not much I can decide or even influence. However, tourist areas in Thailand are in the south, where local bigwigs would not sabotage their own money-making channels. So generally speaking, as long as you don't attract too much attention on the streets and aren’t terribly unlucky, you should be fine. The last time I visited Thailand was in the summer of 2018. The economy seemed to be booming, and there were not many thugs on the streets. Everyone was busy making money. There were some snatch thieves, but they didn't rob me or my friends.

Here are some miscellaneous conclusions, data, and events:

- The more resource-rich a country, the stricter its dictatorial rule, the greater the wealth gap, and the more the rulers hope for mass casualties in natural disasters (South Asia has a relatively higher birth rate, and more deaths mean more aid). They also reject direct foreign aid unless it goes through their own pockets. Examples are abundant: Myanmar earthquakes, Wenchuan earthquake, COVID, U.S. using Pakistan to fight the Taliban, Haiti earthquake, etc.

- Under a dictator's rule, the lower class generally does not rebel. In modern society, especially in Southeast Asia where agriculture is quite good, it is not difficult for the lower class to survive during non-war periods. Anti-government protests or regional organizations are generally led by middle or lower-middle-class people, who take advantage of natural or man-made disasters to gain more supporters.

- The CPI index not only refers to the Consumer Price Index but also the Corruption Perception Index. Myanmar’s CPI is 23 (ranked 157), Laos is 31 (ranked 126), and Thailand is 36 (ranked 101). For comparison, China is 45 (ranked 65). Draw your own conclusions about these countries surrounding Yunnan province hahaha.

- Military dictatorship is the most successful form of dictatorship, and Myanmar's military government is even more unrestrained due to its resources.

- On the early morning of February 1, 2021, Myanmar's armed forces overthrew the National League for Democracy government that had won the 2020 Myanmar parliamentary elections. A few hours after the coup, the Myanmar military announced that power had been transferred to the Commander-in-Chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces, Min Aung Hlaing; Aung San Suu Kyi, the President Win Myint, cabinet members, and leaders of 14 provinces and states were also arrested. Subsequently, nationwide protests against the military coup broke out in Myanmar, demanding the release of arrested leaders and the acknowledgment of election results. Myanmar's military and police suppressed the protesters by directly shooting them (reminds you of Tiananmen Square and events in Iberia, doesn't it? Remember, violent suppression is very common). As of September 1, 2023, a total of 4,029 people were killed due to this military coup, including hundreds of minors under the age of 18.

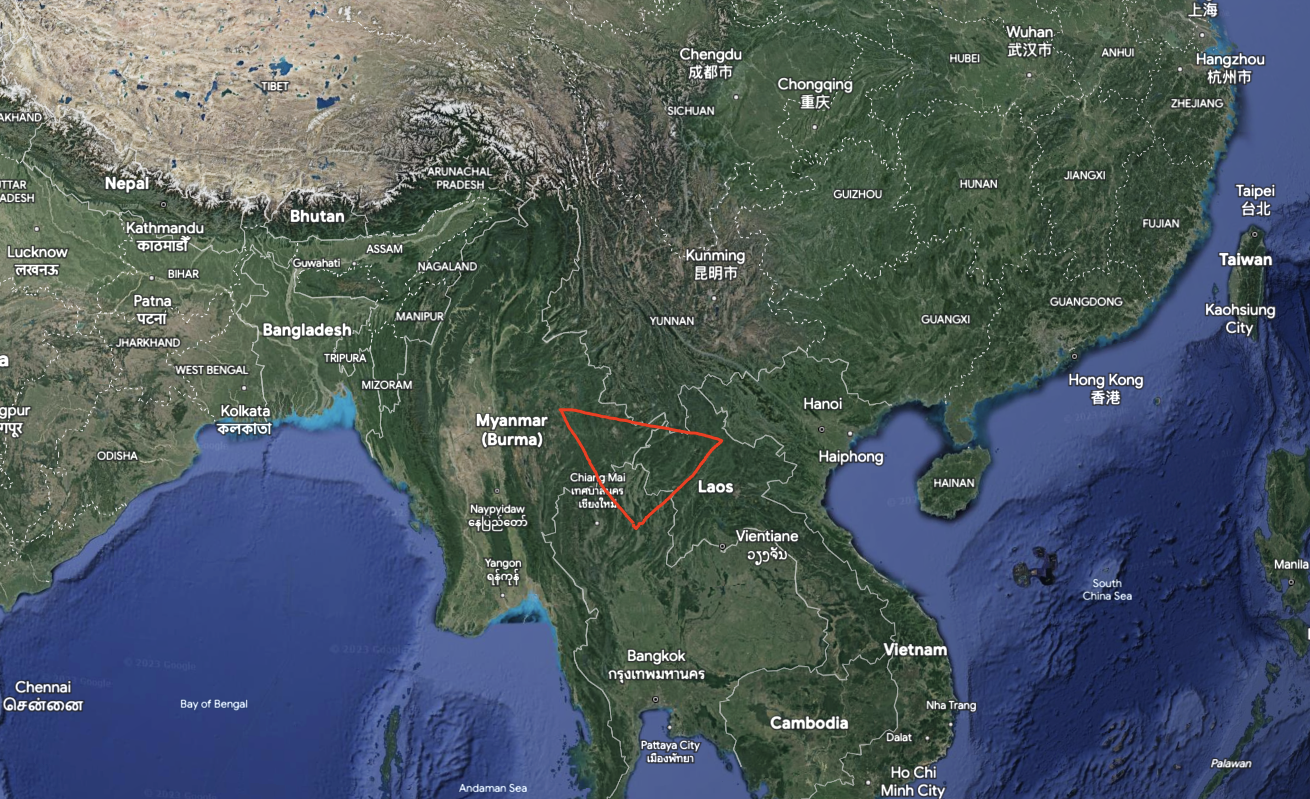

First of all, the Golden Triangle is easy to recognize; it's roughly this area. Anyway, nearby public safety and drug proliferation aren't much better.

In fact, the main reason why Chinese public opinion considers Myanmar to be rampant with fraud is that, compared to our highly digitalized country, they simply have more scammers. However, a more crucial point is that, for a country with a per capita income of only $1,210 (in comparison, China has a per capita income of $12,400 - don't argue about how this average affects you, this data is convincing because the wealth gap in countries like Myanmar is something China can never catch up with), engaging in fraud, or forcing others into it, or letting fraud syndicates operate in one's region, is a profitable job with low costs. It's like the previous trends in our country of selling various game accounts, cheats, or even queuing overnight to buy train tickets for others: many foreigners also find this unbelivable.

Myanmar is not a very high-profile country, not as well-known as Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, or Malaysia, let alone Cambodia. However, Myanmar is the second-largest country in Southeast Asia in terms of land area, next only to Indonesia, and has a population of over 54 million (for comparison, France has around 67 million). It is rich in mineral, oil, and natural gas resources. Myanmar's geographical location is also special, situated between China and India, which undoubtedly strengthens its strategic position in international relations. For dictators, this means more international aid during natural disasters. Yet, we are very unfamiliar with this country. The prevailing impressions are labels like the lawless "Golden Triangle" in the east, rampant drug trafficking, violence, a woman named Aung San Suu Kyi who won a Nobel Peace Prize for reasons unknown, and frequent stints in prison. Then there are the highly active criminal groups today. All these impressions point to Myanmar's biggest feature: chaos. And under the curse of abundant resources, dictators have no incentive to allocate a portion of their alliance's pie for governance. There's simply no need to care about the well-being of the lower classes.

Why is this so? The direct reason for the chaos is: Myanmar is a multi-ethnic country led by a military government. Overall, Myanmar has eight major ethnic groups: Burmese, Shan, Karen, Mon, Rakhine, Kachin, Chin, and Kayah. The Burmese are the most populous, with about 40 million people, followed by the Shan, with over 5 million. The others are relatively small, generally not exceeding 2.5 million. That's not all; there are many sub-groups within each ethnic group. Even the Myanmar government is not clear about it; the official statement says there are 135 ethnic groups. These ethnic groups have been fighting among themselves since gaining independence in 1948, making it the world's longest ongoing civil war: "everyday fighting," so to speak.

So what causes Myanmar's chaos among so many multi-ethnic nations? First, blaming imperialism is definitely not wrong (I'm serious, because no matter how you look at it, past "invasive behaviors" have indirectly led to the current chaos; although no resource-rich dictatorship is without chaos, Britain did invade and did some stupid things, which indirectly contributed). Before becoming a British colony, Myanmar was ruled by the Burmese "Konbaung Dynasty." The Konbaung Dynasty had its ideas and was indeed quite strong (at least stronger than the Qing Dynasty). They were always doing one thing: promoting the integration and unification of various ethnic groups in Myanmar (of course, there's nothing wrong with this; setting aside faith, unification benefits both the public and the dictatorship ruling). Naturally, the methods were rather crude, mainly resorting to military invasions against weaker ethnic groups, particularly the Kachin, Chin, Rakhine, and Karen. These ethnic groups were indeed weak, and some did not even have their own script / written language in the 19th century. The Konbaung Dynasty had good intentions; first, subdue these smaller groups, assimilate them into the Burmese population, and then I can expand my power and go on to deal with the Shan, Mon, and Kayah.

However, just when everything was going smoothly, the British arrived. From 1824 to 1885, it took the British a full 60 years and a heavy toll to completely annihilate the Konbaung Dynasty and subsequently annex the whole of Myanmar. During this process, the British didn't act alone; they had local allies in Myanmar, particularly among the weaker ethnic groups like the Karen, who became their immediate collaborators (employing locals as guides is the best method of invasion, as seen in the Iraq War, Egypt-Israel conflicts, etc.). After taking Myanmar, the British needed to find a local proxy to rule. If they chose the Burmese, they wouldn't trust them, because the British won Myanmar at a heavy cost, and the Burmese were not willing to submit (in other words, they needed a local power that was strong but eternally loyal to them). But if they chose other ethnic groups, they were too weak to control the Burmese. In the end, the British found a solution: they appointed Indians as their proxies. Therefore, Myanmar did not become an independent colony but was incorporated into British India, becoming a province of India, a colony within a colony. Most of the officials and police in Myanmar were Indians, along with a small number of British (George Orwell, the author of 1984, was once sent to Myanmar as a policeman).

The result was predictable. Economically, socially, and religiously, conflicts between the Burmese and Indians were constant. A popular saying in Myanmar at the time was: "If you meet an Indian and a cobra, kill the Indian first." Even so, the British still didn't trust the Burmese, so they suppressed them throughout their rule. For instance, the Burmese couldn't join the Anglo-Burmese army, which was mostly comprised of these minority ethnicities. Many even rose to military nobility. But in the mountainous regions where minorities were the majority, the British still used the traditional local proxy system. As long as the local chieftains of the minority ethnicities respected and obeyed British orders, they could maintain their autonomy (because there are many mountainous regions, this was actually quite common, but both sides knew these areas were not critical, so they didn't take it too seriously).

In short, the British suppressed the Burmese while elevating other minority ethnicities, turning them into the backbone of British colonial rule, the army, and a wealthy bourgeois class, with an overall status even higher than the Burmese. Under British influence, many minority ethnicities even converted to Christianity, gradually forming their unique cultures and further developing their ethnic identities. To some extent, the British must bear responsibility for the chaotic ethnic landscape in Myanmar today. Given this historical backdrop, it's understandable why the Burmese are so bitter, and thus their dictatorial leaders have put forth a slogan: "Return Myanmar to the Burmese; Myanmar belongs to the Burmese." Consequently, the Burmese began practicing ethnic chauvinism against other minority ethnicities. At this time in Myanmar, although the minority ethnicities had been elevated to a high status, they still couldn't compete with the Burmese. If the Burmese wanted to eliminate them, they really had no way to resist.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a nationalist independence movement also emerged in Myanmar. Its leaders were Aung San and U Nu, the former being the father of Aung San Suu Kyi. Their goal was, of course, to resist the British colonizers. Initially, they wanted to collaborate with China, so Aung San set off from Taiwan to Xiamen. However, en route, he was kidnapped by Japanese agents. Somehow, the Japanese convinced him, and he eventually chose to cooperate with them, establishing the "Burma Independence Army" in 1941. In January 1942, the Japanese army, along with the Burma Independence Army, began to attack Myanmar. In summary, seeing the aggressive stance, the British decided to flee. To create chaos, they deliberately left a large amount of weaponry to the minority ethnicities before retreating. Armed and instigated by the British to fight against the Japanese, the Burma Independence Army was extremely annoyed with the minority ethnicities. So, under the banner of anti-colonial rule, they wanted to eliminate them. On the side of the minority ethnicities, they saw the Burma Independence Army as outright "traitors," so under the banner of anti-Japanese resistance, they wanted to eliminate the Burmese. Both sides had strong reasons, and due to the conflicts between the Burmese and other ethnicities during the British colonial period, the hatred was intense. This laid the groundwork for future civil wars.

In the early stages of the war, the Independence Army and the Japanese were at an advantage. So, Japan quickly established a puppet government in Myanmar, led by U Nu. Though a puppet government, it still had some power. U Nu began to implement Burmese nationalism policies, attempting to create a unified culture and ethnicity in Myanmar, aiming to wipe out other ethnicities. However, as World War II progressed, Japan began to falter. In March 1945, when Japan was weakening, Aung San promptly switched sides and collaborated with the Allies. A few months later, Japan surrendered. Although Aung San was initially with the Japanese, as the only influential figure within Myanmar, the British had no choice but to accept him as a negotiating partner. Finally, in 1947, an agreement was reached between Britain and Myanmar, with Britain promising to grant Myanmar independence in 1948.

To give credit where it's due, Aung San was a visionary leader. He clearly understood that Myanmar's ethnic issue was a ticking time bomb that had to be defused for the country (or for his dictatorial regime) to have a future (essentially due to the high cost of governance, as core members of alliances were difficult to win over due to internal conflicts, and the cost of suppressing various factions under each core member was also high). So, after returning from Britain, he immediately invited leaders of various minority ethnic groups to a grand meeting. He persuaded them not to seek independence and promised federal governance with full autonomy for minority regions. Consequently, the Panglong Agreement was signed in February 1947, and a temporary peace was achieved between the Burmese and the minority ethnicities. Their respective armies also merged. However, this good phase didn't last long. Just five months later, Aung San was assassinated by U Saw, another Burmese political leader (this is the downside of managing a nation with many organizations and hard-to-reach mountainous regions...). Myanmar thus lost its most capable political figure, perhaps the only one who could balance various domestic forces.

After Aung San's death, Myanmar did move towards federalism as he had planned, but sadly his successors, whether U Nu or Ne Win, were staunch Burmese nationalists who didn't care about minority ethnicities. Objectively speaking, Aung San was also a Burmese nationalist, for instance, he always denied that the Mon were an independent ethnicity. Ultimately, Aung San, like U Nu and Ne Win, aimed to assimilate other minority ethnicities. The difference was that Aung San was more pragmatic and skilled in the arts of dictatorship and economic management. Others lacked such skills. Whether through cultural assimilation or outright military force, they blatantly exacerbated Myanmar's ethnic tensions, leading to wars that have lasted for over 70 years.

So, the historical reasons for Myanmar's chaos are twofold:

- First, British colonizers disrupted Myanmar's previously smooth nation-building.

- Second, after WWII, Myanmar's leaders ignored that the country is multi-ethnic and multi-religious, focusing solely on creating a nation with a single ethnicity and culture. They severely underestimated the impact of human culture and spiritual/familial beliefs on people’s actions (indeed, many modern theories assume that rational people will choose the best solution from the game theory perspective, but as leaders of a nation where almost everyone has beliefs, they should not ignore the scale of irrational rebellious behavior).

I also want to write about Than Shwe and his time in power (from 1992 to 2011, serving as head of state, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, prime minister, chairman of the development committee, etc.), especially since telecom fraud became widespread around 2010.

As mentioned before, Myanmar has been in civil war almost continuously since its independence in 1948, mostly under military governments. The cost of dictatorship is dealing with numerous rebellions, and dictators rely on the most lucrative industries to fill their own and their alliance members' pockets. In resource-rich Myanmar, the Than Shwe regime did everything possible to keep the population poor, isolated, and ignorant (because he and his alliance did not need to rely on the people to make money). There was no press freedom, gatherings were prohibited, and very few foreigners were allowed to enter (those who did were closely monitored by the police, similar to North Korea) — all to make it difficult for people to organize against the government.

An interesting note (from "The Dictator's Handbook"): About 15 years ago, data showed that Myanmar exported between 1.4 and 1.6 million cubic meters of hardwood annually, a large part of which was the valuable teak, generating an estimated $345 million per year. The term "estimated" is used because exact data is hard to come by. In 2001, China reported importing 514,000 cubic meters of hardwood from Myanmar, while Myanmar's corresponding export data showed only 3,240 cubic meters. The income from unrecorded hardwood exports likely went into the pockets of the generals rather than improving public welfare. In my opinion, only Myanmar could pull this off because pure dictators don't need to pretend; they can openly make money. But in other countries where dictatorship is prevalent, like China, Singapore, or South Korea, this is taboo: leaders must find a secretive way to hide their profits and those of their alliances (it reminds me of a phrase from a movie: "put your money under the carpet" haha).

Myanmar is poor, but Than Shwe is wealthy. He is fortunate because he doesn't have to rely on the labor of the people, allowing him to suppress them ruthlessly. This also means that although the people of Myanmar live in miserable conditions, they are not likely to rebel:

- If they do, Than Shwe has enough resources to buy the loyalty of the army to ensure he stays in power.

- As long as they're not starving to death, not many people will choose to rebel.

Here's an example of Than Shwe's suppression:

In February 2007, a significant protest took place. On August 19th, around 500 demonstrators took to the streets to protest against rising fuel prices, led by student leaders who had participated in the 1988 protests (feels similar to Tiananmen, doesn't it? even close in date). This protest lasted for many days. As the military initiated large-scale arrests, the number of protesters dwindled to hundreds. However, by September, the movement gained momentum again when hundreds of Buddhist monks joined. The military physically assaulted the monks, tying two of them to a lamppost and brutally beating them; reports claimed one was even beaten to death. Given the reverence for monks in Myanmar, this violent treatment triggered further protests (at this point, there might indeed have been situations where people were starving, hence some "failed Zhu Yuanzhangs" appeared haha). Monks from various regions started marching, and the protests escalated. People began to talk about the "Saffron Revolution," named after the color of the monks' robes.

Starting from September 25th, the government ordered a violent crackdown on the demonstrators. Initially, rubber bullets were used, followed by live ammunition. The military also raided temples, arresting numerous monks overnight and driving the rest back to rural areas to prevent them from gathering. Three days later, the protests were entirely quelled. While the Myanmar government succeeded in crushing all opposition through force, it came at a high cost. They were initially worried that the military might hesitate to raid temples. Although they eventually did, it undoubtedly drained a lot of resources to buy such loyalty.

Though brutal, Than Shwe's actions represent exemplary dictatorial politics. He extended his rule: being a leader is more important than being a good leader. In 2019, amid slowing economic growth, the military government specifically introduced a new "Gambling Law," allowing foreigners to legally register and operate casinos in Myanmar, further accelerating online gambling in northern Myanmar (of course, some tolls had to be paid privately).

Thus, the overall living conditions of the people in Myanmar are quite miserable. The government obstructs people from coordinating and communicating, isolating them and diminishing their productivity. Yet, after the suppression, thanks to widespread and efficient agriculture industry, the chances of starving are still not high (well, much better then China 1942 1943 1960 etc.)

In such an environment, with everyone's income being so low that bartering prevails, suddenly some wealthy "capitalists" from China offer excellent wages to lure Myanmar citizens who speak Chinese or directly deceive naive adults into Northern Myanmar for scams. Where else in the world can you find such an ideal place with poor transport, no legal costs for crimes (though some bribery is inevitable), easily bribable government and law enforcement officials, and inexpensive land rents for exploiting the Chinese populace?

- Philippines? African countries? South America? Forget it; any country far away from mainland China is unsuitable for such forced labor businesses because there are too many people to bribe and connections to establish, making it not worth the effort.

- Vietnam? At first glance, it might seem plausible, but upon reflection, it's complicated:

- First, the bosses of such terror organizations need reliable local informants. After all, Vietnam's Corruption Perception Index is 42, ranking 71st, on par with China.

- Second, the income from resources is not as high a proportion as in Thailand and Myanmar, so Vietnam is more "people-oriented."

- Transportation near Hanoi in the north is more developed (I will be transferring flights there at the end of the year haha).

- Since the end of the Second Vietnam War in 1976 and the establishment of the republic, there has not been any significant internal warfare or chaos.

- Over 70% of Vietnamese people have no religious beliefs, making them "relatively" more rational in their choices based on game theory.

- Like Myanmar, Vietnam has many ethnic groups, but thanks to its long coastline and decent economic policies, people are more focused on growing the economic pie.

So the chances of large-scale scam terror groups appearing are indeed low.

As for events in 2021 and beyond, there's really no need for further research and analysis. A change in regime will not bring about significant changes in a few years, and as long as the military's command is solid, there won't be any fundamental changes.

One interesting point we as Chinese might experience later:

After Myanmar's military seized power in February 2021, they started to heavily control the media environment. Internet and phone communications were limited. From February 3rd to 7th, Facebook was blocked nationwide (because FB is Myanmar's most widely used tool), followed by Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp from February 5th. The next day, Myanmar's Ministry of Communication ordered telecommunications operators to stop data services for mobile and fixed lines to prevent people from commenting on social media. NetBlocks reported that Myanmar's internet connectivity dropped to 16% of its normal level that afternoon. Interestingly, the Ministry's orders were dictatorial, but they claimed their actions were in line with Myanmar's "Telecommunications Law," as they were suitable for the national situation. Some internet services were restored after February 7th, but another nationwide internet shutdown occurred on February 14th. Starting from March 15th, the Ministry ordered the closure of all FTTH and Wi-Fi services from March 18th, and the military government required several telecom companies to interrupt wireless internet services on April 2nd. It's said that many small towns still have no internet to this day.