Just read a random book and wrote some related stuff

- The source of samples and sampling methods are extremely important.

- Opinion polls almost always have bias, and often they're intentionally designed to produce desired results (this reminds me of the inflation expectation theory).

- In fact, the mean, median, and mode can all be referred to as “averages”.

- An undefined average is actually meaningless - pay close attention to reports that include averages, there may be ulterior motives.

- The more natural the data (such as height), the closer it is to a normal distribution, so the three types of averages will be closer and harder to manipulate. Clearly, this is not the case for production / society related data.

- The meaning to using small-scale experimental groups is that if the experiment is repeated many times, the probability of accidentally obtaining the results desired by the leader will be very high.

- If discussing a sensitive topic, it's very risky not to declare your position as soon as possible (women's rights? sexuality?).

- Over three-quarters of American farms have "access" to electricity: the real trick in this statement is the word "access," so that government officials can claim it’s his performance. "Access" could mean having electricity, or it can also mean that the cable passes by the farm or is within 10 miles of the farm.

- Rankings without specific numbers are not credible.

- Beware of y-axes that don't start at 0! Some might even excuse this as saving space!

- A social experiment once showed that no matter what incredible fake news (like the Earth being flat) is published in newspapers, about one-fifth of people will believe it (at least on surveys). This tells us that it's entirely possible to manipulate public opinion with carefully crafted charts (government spending skyrocketing!).

- Make sure to check whether the y-axis is a uniform distribution or an exponential distribution!

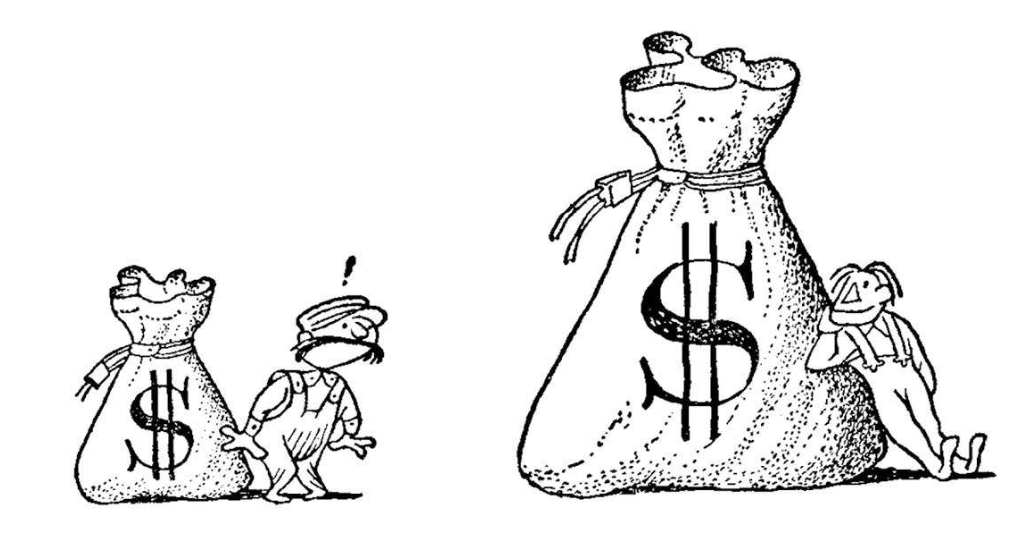

- Beware of images! If both the length and width are doubled, it feels like it's 8 times (3D)!

-

When data compares multiple things, be careful that these data might seem related but might actually be unrelated (even if related, it's not necessarily causative).

-

In the design of survey questionnaires, adding a question may affect the overall responses. For example, asking if you discriminate against black people in the first question and then asking if you think black people have lower employment fairness than white people, will make it more likely to get equal employment opportunities as the response, due to psychological suggestion.

-

When someone says he can do 30% more work, be sure to find out who he is comparing to!

-

There are many ways to describe data. For example, to describe the same thing, it can be said as a 1% sales profit margin, or 15% return on investment, or 10 million dollars in profit, or a 40% increase in profits (compared to the average level from 1935 to 1939), or a 60% decrease compared to last year.

-

When comparing two graphs, focus only on the subject you want to conclude about and exclude all other interfering factors (e.g., photos of women's hair with and without shampoo - exclude factors like lighting).

-

About percentages: Any percentage derived from a small sample is misleading. It's better to give the original data. If the percentage is precise to decimals, it's not just stupidity, it's deception.

-

"Buy Christmas gifts now so that you can save 100% your money," this sentence can actually be true because if you buy gifts at half price now, compared to buying them closer to Christmas, you really do save 100%. Similarly, you can say: "the decrease ranges from 14% to 220%," if you think anything over 100% is suspicious, choose a number between 0 and 70.

*This calculation is easy, assuming the original price is 1, the real discount is d, and the fake discount is k, then (1-d) k + (1-d) = 1, so d = k / (1+k). So if you want to say the price dropped by 220%, you put k=220% in, and the real discount is: d=68.75%.**

-

Percentages usually cannot be added! If every cost of publishing a book increases by about 10%, then the total cost should also increase by 10%, not the sum of the individual percentages!

-

Most companies in China claim in their recruitment ads that the average monthly salary is a certain amount, which is 100% false because it includes overtime pay (of course, getting overtime pay in China is actually not common since most companies don’t respect laws, haha).

-

In statistics related to employee wages, remember to take into considerations of many part-time workers or interns.

-

Regarding the price manipulation of goods, the common tactic is to choose an appropriate base number: Item A was 20 last year and is 10 this year, Item B was 5 last year and is 10 this year. So if last year is the base (100%), this year A's price becomes 50%, B's price becomes 200%, and the average is 125%, i.e., prices increased by 25%. But if this year is the base, A's price last year was 200%, B's price was 50%, and the average was 125%, so last year's prices were 25% higher than this year's, i.e., this year's prices fell by 25%. Of course, geometric mean can solve this problem, but people still use this trick to fool others.

-

How to avoid being fooled:

- When you see the word "expert," first determine whether this person is an authority or just related.

- Look at the speaker and analyse the interest related to his analysis.

- Think: how does he know these data and conclusions?

- Is the sample size large enough?

- What's the definition of "average"?

- What might be missing? The data might be true, but what if they don’t show you all they got?

- Think of the scale of sample behind the percentage.

- Think of possible outliers in the sample.

- Think of the bases of the 2 percentages which were used to make comparison.

- Think of the periodical patterns or special events (especially in economic data, like public holidays etc.) when making comparison

- Consider whether there has been a bait-and-switch between the original data and the final conclusion: Have the concepts been switched? Have we mistaken one thing for another? A common tactic is to use mental inertia for substitution. For example, an increase in the reported number of cases of a particular disease does not necessarily mean that more people are getting sick. It could be that the reporting system has improved. Similarly, an increase in reports of robbery may simply be because two reporters are trying to get more views. The official count may not have increased.

- Consider whether the statistical caliber has changed: For example, if the number of farms this year is 500,000 more than in previous years, the conclusion that people are now more interested in returning to farming assumes that the number of people returning to farming has also increased in proportion and that the criteria for determining what constitutes a farm have not changed.

- Consider the purpose of the data collection after the statistics: For disaster relief and central government assistance, population counts may be inflated (this is also why China has a household registration system that is so rigid). For tax and conscription purposes, numbers may be underreported.

- Consider a company that claims to be number one: In what aspect are they claiming to be first? Is this aspect widely accepted and important?

- Consider how data that shouldn't be precise to the decimal point can be calculated to the decimal point: Think about how a data point that shouldn't be able to be calculated down to a decimal point was calculated with that level of precision