I was inspired to write this after recently studying the liquidity risk section of the FRM (Financial Risk Manager) program, where there's a subsection on "funding liquidity risk." It mentions how some institutions profit by borrowing short-term to invest long-term, commonly known as maturity transformation. Others engage in liquidity transformation, buying assets with poor liquidity and selling those with good liquidity to earn a premium. There's also credit transformation, which involves buying assets with bad credit quality and selling those with better credit.

The reason for discussing this is that it directly links to the economic growth of the past several decades, mediated by modern banks. In a nutshell, the economic growth in these decades has relied on borrowing short and lending long, betting on low short-term interest rates and higher long-term yield across countries and regions.

Let's Discuss the Past Money-Making Logic

To break it down, in the past 20 years, one could profit from real estate; in the past 10 years, it was through the internet. The core reasons are either achieving a sufficiently low short-term borrowing cost or securing a high long-term investment return.

- Having a low short-term borrowing cost requires a loose monetary policy.

- Achieving high long-term investment returns necessitates excessive money supply paired with significant asset bubbles.

In the late 1980s, when Greenspan took office, he immediately shifted the economic landscape by embracing inflation, advocating the concept of moderate inflation. He believed that an inflation rate of 2-3% was appropriate, meaning that there was no need for high interest rates. In the early 1990s, substantial rate cuts began, significantly reducing the short-term cost of money. Moreover, with Greenspan's monetary easing combined with the rise of the internet and the information technology revolution, there was rampant bubble inflation. This surge contributed to the growth in corporate valuations. From then on, asset prices worldwide began to be influenced less by current cash flows and profit levels, and more by future expectations. But this shift was reasonable, considering that previous strategies were overly conservative, focusing too much on present circumstances.

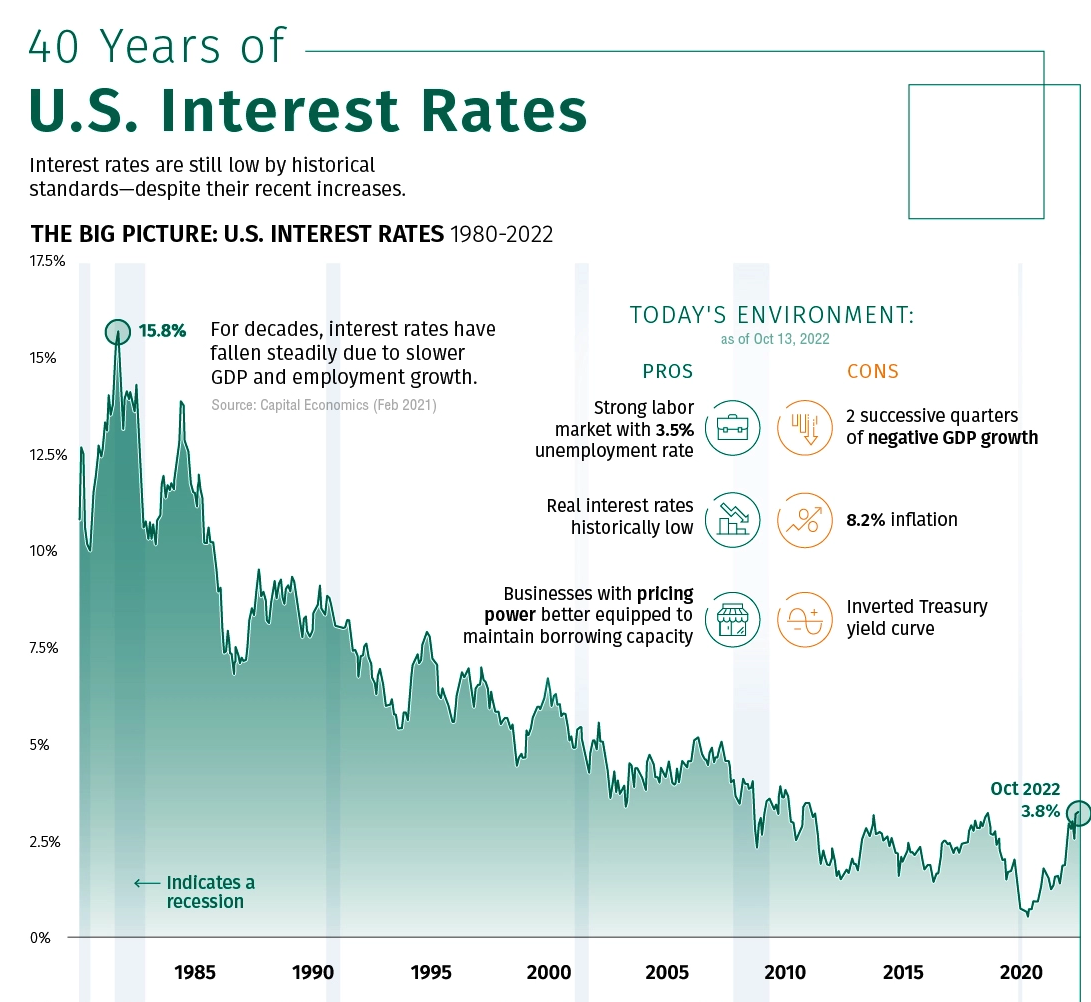

Therefore, after the 1990s, borrowing short-term, investing long-term, and speculating on valuations became the quickest way to make money. This trend can be distinctly observed in U.S. bonds. From the 1990s, the short-term yield on U.S. government bonds was consistently lower than the long-term yield. Simultaneously, a high long-term yield implied high long-term monetary usage costs. Therefore, borrowing long to invest long was not advisable, leading investors to focus on short-term borrowing.

To simplify: If I borrow 100,000 units from a bank, and the bank offers a 1% interest rate if paid back within a year or a 3% rate if repaid in ten years, I'd choose to repay within a year under the assumption of a lenient market. I could then reborrow the 100,000 units, effectively earning a consistent 2% over ten years.

Thus, a consistent difference between short-term and long-term interest rates is an excellent arbitrage opportunity. This strategy is virtually risk-free, unless systemic crises (like government interventions) occur. It's a bet on whether the government dares to risk an economic slowdown or a bursting bubble.

The logic of making money over the past 30 years essentially hinges on this concept, although the methods vary. From P2P platforms (evidently borrowing short and investing long by attracting public deposits to aggressively invest in "bullish long-term assets") to real estate (leveraged arbitrage) and even Bitcoin (capitalizing on valuation bubbles) and the Metaverse (initially a narrative for a highly stressed Meta, aiming to inflate another bubble). In essence, all players, whether institutional or retail, are gambling on the persistent difference between short- and long-term costs. Aiming to profit from both interest differentials and asset appreciation is somewhat greedy.

Real estate and the internet became booming industries because the excess liquidity in the market favored them. Real estate emphasized high-turnover leveraged arbitrage. By using large amounts of cheap short-term debt and constantly borrowing new to repay old, it led to the formation of low-interest long-term debt. This enabled nearly cost-free land development, and with no costs, developers could leverage even more aggressively.

Both Evergrande and Sunac primarily faltered due to short-term debt defaults. The significant debt of most real estate companies is short-term because only this type of roll-over financing is profitable. It brings to mind a case from the CFA about Northern Rock's strategy of borrowing short and investing long — a universal approach among many. Thus, real estate developers aren't necessarily concerned about the actual value of properties or even if prices increase. As long as their operations run smoothly and they can leverage efficiently, the profits will be substantial.

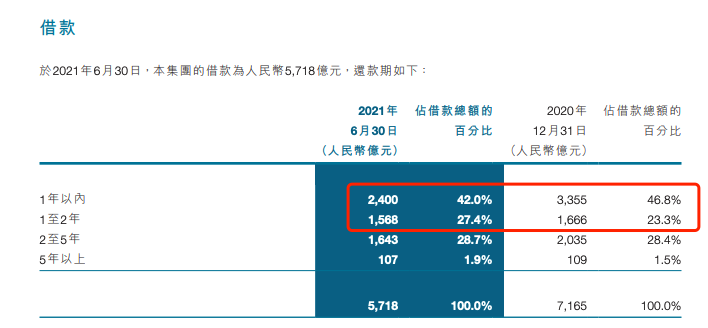

On a side note, according to Evergrande's latest mid-2021 report (yes, it's been two years since the Evergrande crisis... time flies), nearly half of their loans are short-term.

Evergrande's Mid-Year Report on Borrowing from 2009:

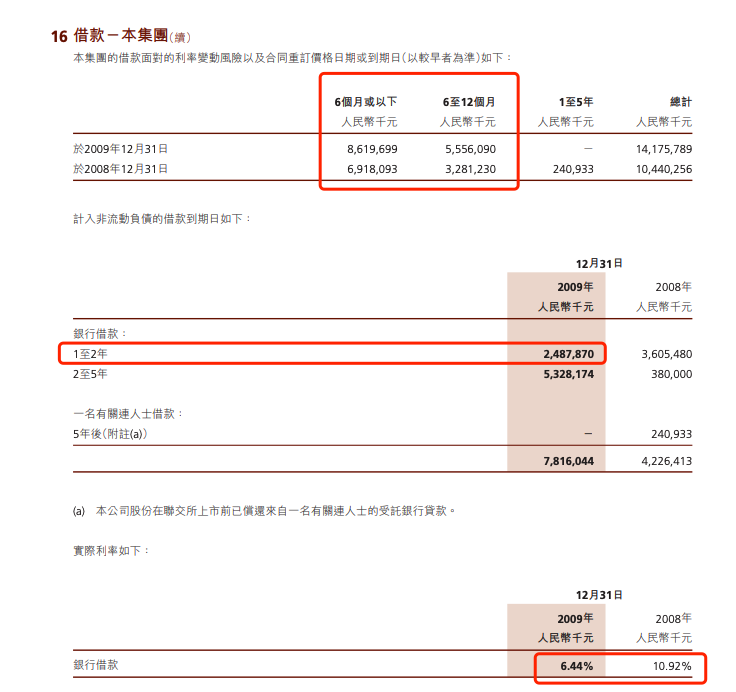

From the chart, short-term non-bank borrowing (within 1 year) accounted for 100%! Although Evergrande began its aggressive land acquisitions only after the Spring Festival of 2009, borrowing 140 billion in one go that year was quite audacious.

The internet sector differs slightly, relying more on storytelling - leveraging the potential future appreciation of their assets to acquire wealth today. By presenting a compelling narrative, they hype up the long-term returns on assets such as stock prices, and then monetize, converting future possibilities into present-day cash. This is why presentations are so critical, as evidenced by startups like shared bikes and unmanned supermarkets.

Even by 2018, after Jerome Powell took charge, the strategy of borrowing short and investing long remained viable. The Federal Reserve's policies, in whatever form, still aimed to ensure that short-term returns were lower than long-term ones. Whenever the economy faltered, with the possibility of long-term bond yields dropping below short-term ones, the Fed would cut interest rates and relax policies to maintain relatively low short-term rates.

This approach has been adopted numerous times. Thus, the financial world has been conditioned to expect that, at the first sign of recession, the Fed would step in with monetary easing. It's seen as a rare opportunity to leverage and capitalize on the interest rate differentials, anticipating the Fed's actions. And when the yields on short and long-term U.S. Treasury bonds invert, it's the market betting on a recession, pressuring the Fed to cut rates. This strategy has worked for thirty years.

However, by July 2022, when another recession hit, investors started shorting short-term bonds, leading to an inverted yield curve. But the Fed's response seemed unexpectedly stringent, not conceding for so long that the inversion even peaked at 130 basis points, the largest since World War II. In other words, Wall Street had been warning of a recession for 7 months, but the Fed remained unmoved, keeping rates high. Gradually, the financial world was feeling the strain, particularly with the rising cost of short-term debt draining their profits. Property developers found their borrowing costs surpassing profit margins, and internet companies realized that, regardless of how captivating their stories were, they couldn’t outpace the bursting of their valuation bubbles.

Could we use this theory to whimsically explain the unexpected performance of the S&P 500 and NASDAQ in August 2022? (Just kidding, lol!)

Jerome Powell was evidently concerned. Despite his hints, the rate hikes didn't significantly alleviate inflation. (Honestly, wouldn’t it be better to drastically raise rates by 10%, resetting the system?) The Fed was thus forced to postpone its rate hikes and cuts. The report available online from the Federal Reserve, which includes potential future rate probabilities, has been notably delayed recently.

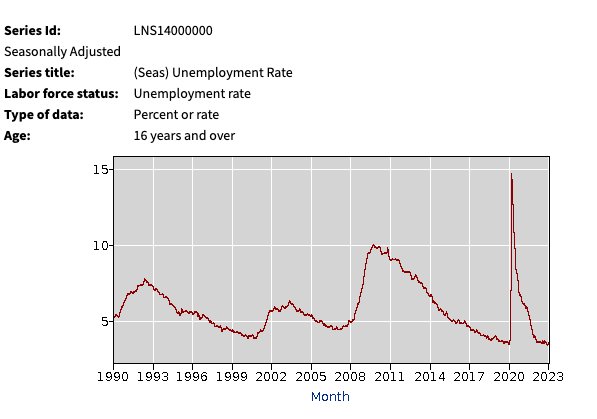

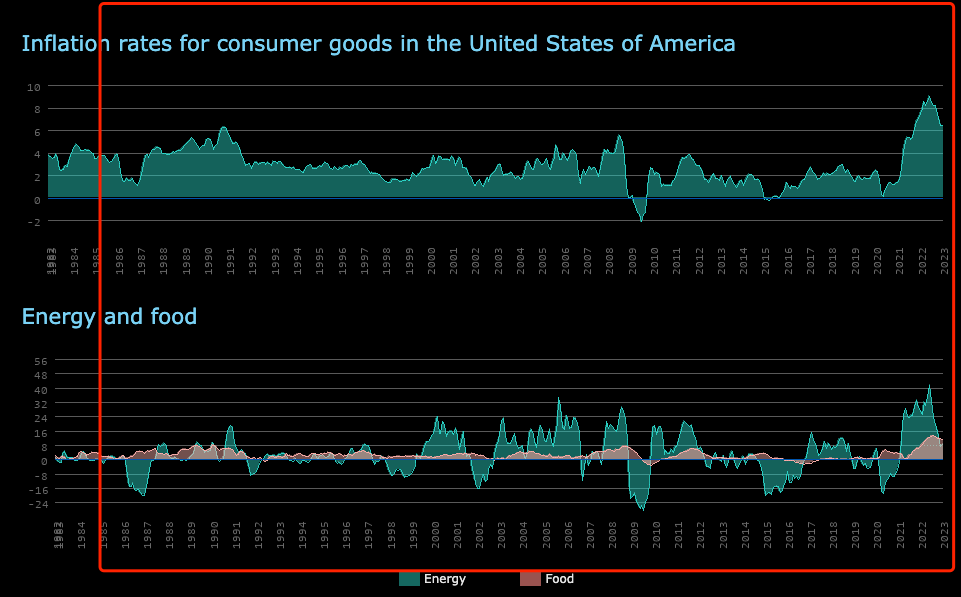

Discussing the Industry Changes Making Things Tough for the U.S.

For the past 30 years, innovations and automation have propelled the U.S. forward. Post-1990s, the U.S. barely faced high inflation, due to its vast market and the strength of the dollar. Globalization, coupled with hollowed-out and automated industries, kept U.S. unemployment relatively high (though it's notably low recently). The accompanying chart is based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Statistics, focusing on inflation and interest rates. There is no need to judge its authenticity as long as the market believes in these figures.

The numbers in the middle represent the inflation rates announced over the past few decades, while the numbers below indicate interest rates.

Recently, major nations have encountered obstacles. Countries with the capability have started to revert from globalization, with the U.S. leading the push for "industry return". The technology dividend reaching its peak, and the entrapment of vast U.S. dollars domestically, has been a primary reason for the persistent inflation. The actual decline in inflation is much slower than expected. This phenomenon, termed "expected inflation" in economics, suggests that if people believe inflation will rise, it indeed will. This is why Powell, despite knowing the reality, still optimistically predicted a controllable 5.5% inflation rate for early 2022.

The current inflation isn’t something the Federal Reserve can easily tackle through rate hikes alone. They’re battling against de-globalization and technological stagnation. They may be forced into unexpectedly long monetary contractions to curb inflation, which would lead to plummeting long-term asset yields and valuations and rising short-term borrowing costs. Consequently, leverage and financing might diminish, leading to many internet companies collapsing. Money would flow back to tangible businesses, emphasizing cash flows and reverting to the strategies of the 70s and 80s. It won't be about storytelling but about business fortresses. So, don't blindly invest in companies like Boeing, General Motors, or IBM; they might not even outperform Tesla. After all, Elon Musk has brilliantly transitioned Tesla from a pure storytelling venture to a tangible economic entity.

The distress caused by this issue is not limited to the United States, as U.S. Treasury bonds are a global valuation benchmark. China's macro leverage rate at the end of 2022 is 273.2% (data from the Securities Times, here), while the U.S.'s is 264.6%. Breaking down the figures, China's government leverage is at 50%, and the U.S. government's is 135%; Chinese enterprises' leverage is at 137%, while U.S. companies are at 64%. In the matter of leverage, the U.S. government is the main borrower, while in China, it's the enterprises and individuals. The risk-bearing capacity of debt holders in the U.S. and China can't be compared. To spur economic recovery, China had to resort to expansive M2 and real estate stimulation policies. Part of the reason for the current situation can be attributed to the recent interest rate hikes and cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve, which was in conflict with our economic development timeline. (My view is, China shouldn’t pose the sanctions because of COVID that fast, because it could only rupture the tie with the world. Since Chinese economy is not that good, if it can’t be NO.1 in the world then it has to bear more pain when other countries are at pain)

Specifically, after the pandemic, the Federal Reserve implemented a significant stimulus, benefiting businesses in the U.S. and other countries. Still, China suffered. China's epidemic prevention policies didn't allow Chinese enterprises to benefit from the U.S. dollar's expansion. It's worth noting that the U.S. dollar can't freely circulate in China. Hence, even if many private and state-owned enterprises saw a surge in orders and profits, in reality, these dollars can't enter state-owned enterprises. Consequently, the excess U.S. dollars, after the Federal Reserve's massive printing, largely went to private enterprises.

Foreign investment is a crucial driver for economic recovery. But two years ago, China didn't benefit from it. When China chose to liberalize its economy nine months later, the Fed's tightening had just peaked. The inflow of "hot money" from abroad had already dwindled due to prolonged interest rate hikes. What foreign investments remained? Such shortsighted Chinese leaders! They wish to promote the A-Share “registration system” (registration-based IPO regime), but without genuine foreign investment, how much capital will follow? (Although during that period, northbound capital (referring to money flowing to mainland China from Hong Kong (usually international capital mixed with some mainland capital that are used for controlling the market)) did surge much more than before, I recall news reports stating that the net inflow in just two weeks had surpassed the total annual figure of 22 years. However, it's worth noting how much of this northbound capital is genuinely foreign capital. My personal estimation is that it might be around 30% at most. This figure is derived by taking 20% of the global capital flow allocated to China and assuming that all of it is invested in mainland stock markets. This means that even if all global capital flow was invested in the A-share market, it would only account for 30%. Of course, this estimation is quite rough and shouldn't be relied upon in practical scenarios.)

Over the past three years of epidemic prevention, many companies and individuals have collapsed, and consumption capacity has been devastated. Some became richer, but many more faced hardships. To stimulate the economy in the face of anti-globalization (and also to meet President Xi's domestic circulation goals - “we demand, we manufacture, and we consume” model), China had no choice but to implement counter-cyclical measures, such as reducing interest rates and injecting liquidity. However, this move hasn't had the desired effect.

In my view, our counter-cyclical interest rate cuts are a gamble on when the Federal Reserve will cut rates. But if the Fed stretches out its strategy and doesn't follow expectations, our minor real estate recovery, spurred by our liquidity measures, could quickly collapse – bad news for current homebuyers. The real estate industry relies on short-term borrowing with low costs. Now, with increasing costs and diminishing returns, how many developers are willing to purchase land? Isn't this why land auctions have recently been cold? If land prices are administratively ordered not to drop, leading to near-zero liquidity, the long-term risk of no liquidity is the ticking time bomb for China's wealth reservoir.

Most Chinese have never experienced monetary contraction. Since the 1990s, we've been in a state of currency over-issuance. With current mortgage interest rates at 6-7%, few can afford them. Can you imagine rates reaching 20% like in Paul Volcker's era? Evergrande couldn't even honor its 9% commercial paper interest rate. High interest rates alone are damaging to modern economies, but the extremely pessimistic expectations they bring are even more devastating. Prolonged negative expectations would lead to massive undervaluation. If we reach deep into this undervaluation, evaporating hundreds of trillions daily wouldn't be surprising.

The Future

In the upcoming years, we are likely to witness a major reshuffling in the business landscape. For a certain period afterwards, companies with stable cash flows, protective barriers, and a loyal customer base will thrive. The trend of industries becoming increasingly financialized will gradually wane, hence there is a pressing need to refresh our analytical approaches! After all, an economy driven by debt has only been around for twenty to thirty years (and only forty years in the U.S.). The economic rebound of the 1980s was primarily propelled by technological advancements, creating an immense new demand and reservoir. However, at this moment, I'm still pondering: which industries or directions can absorb the capital squeezed out by reducing valuations and leveraging? Renewable energy might be one, but it's unfortunate that its development is still in the early stages, so its scale might not be large enough by the time the flood of money arrives.

To address the article's title regarding whether the turning point has arrived, I personally believe the turning point for "borrowing short and investing long" came a while ago. Yet, this is just a blip in human history. As decades roll by, new growth points will emerge. The occasional shake-ups are necessary. After all, "bears last longer than bulls" is a fundamental truth.

On a side note, I feel that China's inflation rate is much higher than perceived. Every time I see a 2-3% figure, I'm inclined to chuckle. Has the local cost of living only increased by 2-3%? Of course, experts might counter my assertion, pointing out that inflation, cost of living, and purchasing power are distinct concepts. From my vantage point, consumer products' prices might be rising at a rate of about 20% annually. For instance, why has the spicy hot pot street food declined in popularity? Because it's expensive. Why, despite stagnant wages, are prices surging? It's because businesses need profits. Why are businesses increasingly desperate for higher profits? Since the strategy of borrowing short to invest long and hiking valuations for financing is no longer feasible, they resort to raising prices! There are other reasons, such as higher land rental costs (which might have increased by just a third of product pricing), but isn't that essentially landlords marking up their "product"? Similarly, we've seen the disappearance of traditional noodle shops, the closure of popular chain restaurants, wealthy people moving abroad, and so on. Funny enough, all my examples are food-related. Even when examining raw materials, prices have only slightly risen compared to previous years. Yet, for the general public, the inflation is considerably higher than 2-3%. And with many lacking disposable income and unable to consume, businesses could only resort to short-term profit strategies.

If the entire economy collapses in the future and everyone becomes paranoid, please don't say that the only lesson humans ever learn is that they never learn. After all, humans operate based on game theory. It's in human nature to be shortsighted in decision-making. Who can blame us, considering our inevitable life cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death?